What do you think of when you think about mapping coastal restoration?

You probably think about locations in the natural landscape. Things like oyster reefs and how they function to make the entire ecosystem function. Things like living shorelines that help protect our coasts. Things like wave action, boat wakes, boat traffic, and how these phenomena impact coastal environments. You might even think about the need to protect marine life with enhanced restoration priorities. The what and the where probably driver your thinking.

But you might think less about how humans think about restoration priorities and where these priorities are located. Where do community members want to see restoration occur? Why do they want to see it happen there? What draws them to a location, giving it value, creating a sense of place? What are the motivations for restoration in that location? And how does their emotional attachment or sense of place connect to their restoration priorities. What drives their decisions? And where do these decisions occur?

As part of our multi-year collaboration on a NSF research grant, our team worked with community partners, biologists, engineers, and students to understand coastal connections and sense of place in the Indian River Lagoon, Florida.

What did we map? Our GIS work on the project helped map sense of place in fundamental ways. First, by utilizing GIS methods to analyze community-based information about stakeholder perceptions we are able to highlight the knowledge of community stakeholders in the process of coastal restoration. Our framework allows human systems level data from participants mapped in GIS to inform future restoration work in the study site. It prioritizes areas where individuals feel a high emotional attachment to geographic locations as a measure of sense of place.

Why does this matter to coastal restoration? By engaging stakeholders during initial data collection efforts to document and visualize sense of place priority areas, important information was collected to analyze and understand the influence of sense of place and place attachment on stakeholder’s feelings regarding coastal restoration. This inclusion of human systems data from stakeholders on their thoughts, feelings, and reasonings in the process of developing future restoration projects can balance the priorities of science teams and the individuals who inhabit these geographic locations.

You might remember our online mapping applications where IRL community members and visitors shared their knowledge about the Lagoon and their emotional attachment to it. You can revisit that map here to check out the data that was entered.

View the map here: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/mapviewer/index.html?webmap=7b715474741a449abcdb356697b8544a

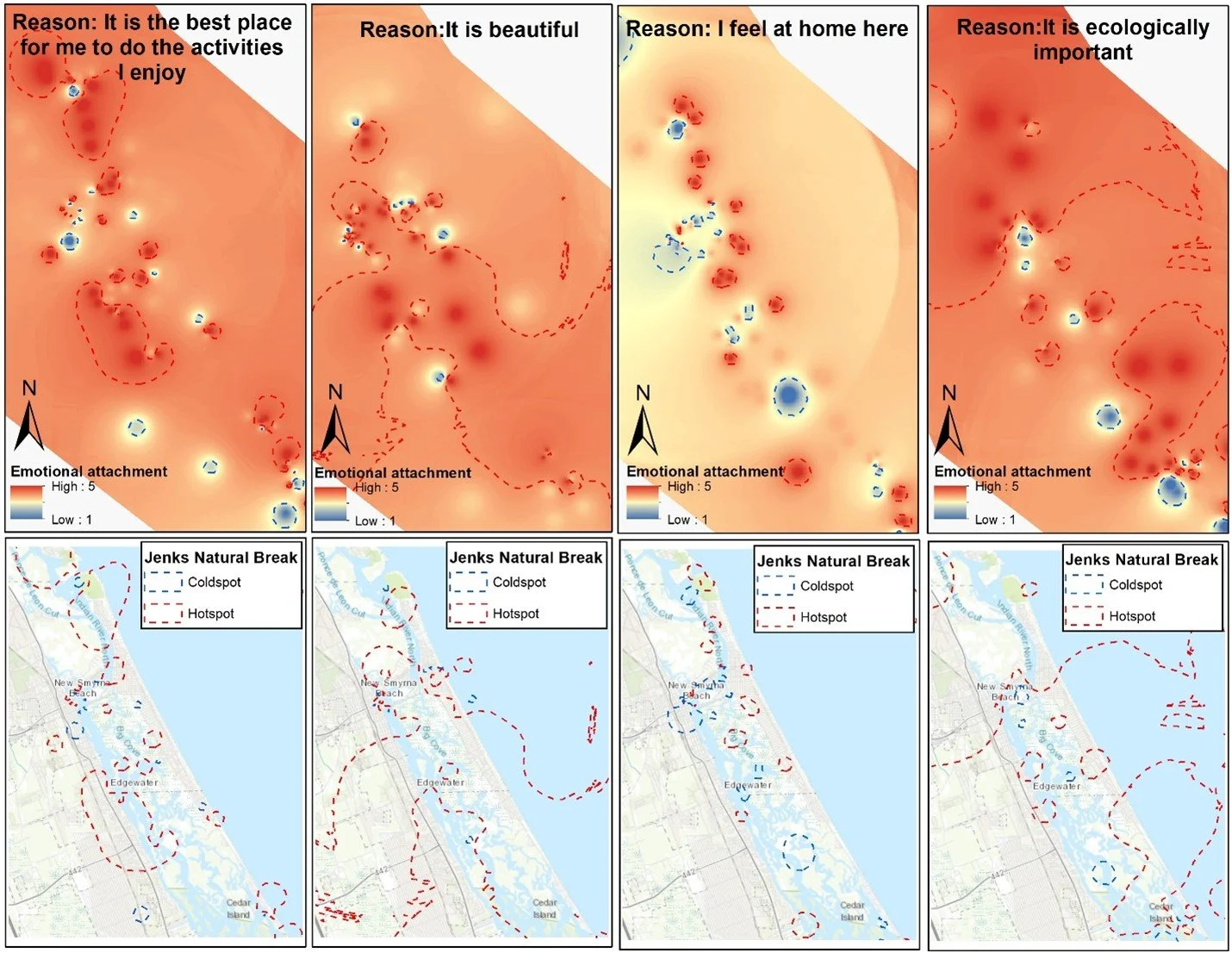

Those data points entered by community members led us to images and mapped data like below that show mapped hotspots of high and low restoration priority when one considers emotional attachment data.

Figure 1: Sense of Place Mapping Results (all participant points) for Indian River Lagoon. Kernel density mapped on left; inverse distance weighted interpolation mapped on right.

Figure 2: Map of points highlighting individual reasons for emotional attachment in Indian River Lagoon

The Next Generation of Science with Education

In addition to the research we were able to support the next generation of science and the next generation of our geospatial technology industry. Over the years of the grant, we supported the next generation of science at UCF by graduating several amazing undergraduate and graduate students, we saw two post-doctoral scholars go on to new faculty and staff careers at two major US research universities, and we launched a successful K-12 education effort with our Maps, Apps, and Drones Tour and now GeoBus that served over 10,000 students, families and teachers in community events, school visits and teacher workshops.

Figure 3: Some of our previous field team members supported by the grant.

Figure 4: One of our teacher workshops from early in the grant.

And all of this happened with a bit of a COVID pause in the latter half of the grant work where working with communities was nearly impossible due to health restrictions.

It’s been a rewarding, challenging and exciting time working at the intersection of multiple disciplines.

At the end of the day, we take great pride in the community partners, educators and students who worked with us to map emotional attachment and sense of place, and to use GIS, maps, and drones to understand Florida landscapes, particularly Florida coastal communities.

While our work is complete in this NSF project, we are excited to move forward in new ways with our partners in related projects that connect science and society.

For more information about our work, please contact Dr. Timothy L. Hawthorne at timothy.hawthorne[at]ucf.edu.